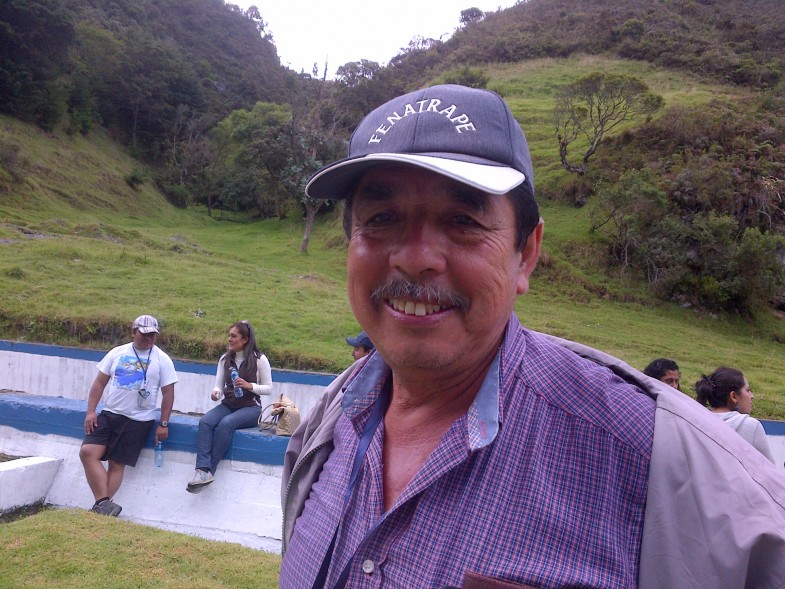

Arturo Quevedo, the engineer responsible for the watershed protection program for Loja, Ecuador’s municipal water agency, has a kind demeanor. His slightly crooked front teeth are prominent beneath his moustache as he waxes ebullient about clean water percolating through forested slopes, coursing through pipes, and hydrating Loja’s children. But don’t let the gentle, nature-lover exterior fool you. As tender as he is with the landscape, he is equally fierce in sniffing out water-polluting scum.

In the 1990’s, Loja’s mayor, José Reyes Jaramillo, faced a city administrator’s nightmare – a diminishing and polluted water supply. This same nightmare haunts cities around the world as climate change makes water cycles unpredictable. While 3.8 billion people get their drinking water from a piped connection, many consumers don’t trust the water. Millions of poor families in megacities like Mexico City, for example, pay a water bill but nevertheless purchase expensive bottled water as insurance against diarrhea and other water-borne diseases.

Mayor Jaramillo’s hunch was that the water problem lay upstream, where swelling cattle herds pounded the earth into cement and abundant manure was a vector for microbes. He turned to Arturo Quevedo, who not only had a reputation for water engineering, but for knowing a thing or two about managing community problems.

“I tromped up ravines and gullies to find the headwaters of the city’s water,” Arturo said. “I inventoried water sources and contaminants.” He recorded how land was used--did it have forest cover, was it over-grazed? “Back then,” he explained, “looking at micro-watersheds and land use together was a new way of seeing.” In many places, it still is.

Arturo pleaded with city hall to buy a 500-hectare (1230-acre) hillside that acts as one of many natural filters for the city’s water. Planners these days refer to relying on natural systems as ‘green’ infrastructure (in contrast to “gray” infrastructure such as a water filtration plant). “Some people criticized me, but I said, look, we don’t have regulations on land use, no ordinances.” From Arturo’s point of view, the best path to clean drinking water without requiring a lot of chemical treatment was for the city to acquire property and fence out cattle. To this day, Arturo remains skeptical about cutting deals with landowners. “You help them reforest and they’re happy with the saplings. But when the trees mature, they screw the program and chop them down for sale.”

A researcher at the watershed conference, Leander Raes, took a slightly different approach, debating Arturo. While his research found that purchasing land for conservation does indeed improve water quality, it doesn’t do much to alleviate rural poverty. The long-term solution, Raes suggested, is to provide an economic boost to small farmers while steering them towards more environmentally-friendly practices--through what are called in present day lingo, payments for environmental services. Others argue that there’s no solution to watershed health in cattle country without making peace with ranchers. Agro-forestry techniques on grazing lands are gaining traction throughout Latin America. Municipally-owned parcels, Raes said, can be a helpful complement but don’t resolve how to incentivize farmers and ranchers to shift away from harmful land and water use.

Loja’s example inspired five neighboring municipalities to join hands through the Fondo Regional de Agua (FORAGUA), an inter-municipal watershed protection consortium. Many watersheds in the region are shared among cities. FORAGUA works with these cities’ mayors to contribute to a pooled conservation fund and write water protection ordinances based on common principles that can be adopted by their municipality. Today, 17 additional municipalities want to join. FORAGUA has aspirations to organize all 39 municipalities in Southern Ecuador.

SENAGUA is Ecuador’s new water regulatory agency. It was created shortly after Ecuador’s 2009 constitution affirmed both the human right to water and nature’s right to water. Those rights are highly popular among Ecuador’s citizens, but not surprisingly also threaten vested interests. FORAGUA recently organized a watershed conference entitled, “New Challenges in Water Management” at the Private Technical University of Loja. Juan Pablo Martinez, Sub-Secretary of Santiago for SENAGUA, summed up the agency’s work in few words, “Managing water is managing conflicts.” Heads nodded in knowing agreement. Arturo was one of them.

The technical director for FORAGUA Francisco Gordillo, an ex-mining engineer, said “I’m paying back my sins against the earth.” He still maintains a miner’s eye; while we walk, he pockets a glinty stone for inspection with a magnifying glass. He runs a side business, renting out mining equipment and dishing out “green mining” advice -- considered by some as “green washing” -- to minimize damage to the ecology.“As FORAGUA, we explain to the mayors that if you protect your watershed upstream, you’ll use fewer treatment chemicals,” Gordillo said. “The quality of life of your constituents will improve. It’s smart politics.” Gordillo works closely with Quevedo who deploys his water engineers in neighboring cities to teach why and how to protect water quality. Still, watershed conservation is not a priority in all municipalities. “The mayors tell me,” said Gordillio, “‘conversation doesn’t win me votes. Grey infrastructure does’.”

To pay for the conservation work -- a combination of community education, land purchase and landscape restoration -- each municipality collects an environmental tax on drinking water charges and sends the revenue to a bank account co-managed with FORAGUA.

“We have had this problem,” explained Arturo Quevedo, “that the water fees coming into the cities might be used to pay off other municipal expenses. We needed to lock up some of that money to protect water supplies. So we set up a trust fund through FORAGUA with an account at the Central Bank.” With Gordillo’s assistance, the mayors sign 80 year contracts with FORAGUA. The environmental tax enters the common inter-municipal kitty, from which even a newly elected anti-environmental mayor can’t back out. These funds are principally used for conservation work in each municipality, with 10% assigned to common projects carried out by FORAGUA.

Gordillo is proud of FORAGUA’s accomplishments; it’s no easy feat to broker cooperation with politicians from competing parties. But it's important. Civic participation is fundamental to monitor compliance. Gordillo pointed out a conga line to me -- hundreds of students puffing up a hillside, each with sapling in hand. “There goes the new generation of water protectors,” Gordillo said. They're part of reforestation brigades that make Loja’s high quality water possible.

FORAGUA thrives in a country where the virtues of environmental protection are splashed across highway billboards. The strong –- too strong for some -- central government uses its propaganda machine to promote water citizenship. “We have a perfect legal framework for this work,” Francisco marvels. Article 411 of the constitution, for example, reads, “the State guarantees the conservation, recovery and integrated management of water resources.”

It’s not hard to find contradictions. While the government recognizes the centrality of rural communities in stewarding the landscape, local autonomy is a delicate dance in Ecuador. The country is almost as diverse in culture and ethnicity as it is in flora and fauna. Thousands of communities, many indigenous, manage their water systems independent of public agencies. The government doesn’t always respect those local systems, especially when they sit atop mineral and petroleum deposits that the government offers as concessions to mining and petroleum companies. The government would like greater oversight over water funds like FORAGUA. They would like the more than half dozen water funds in the country—led by the Nature Conservancy and others—to preserve a public character.

“This isn’t easy work,” Quevedo said. “I’ve had to go head to head with a Supreme Court judge who owned land important for Loja’s water quality. I got him to talk to us and eventually to sell.” In another showdown, with a mob of angry citizens behind him Arturo shamed a well-connected landowner into selling his over-grazed land. On that day bees from nearby hives –- Loja’s water company operates a side honey business –- got spooked and swarmed the crowd, scattering people in all directions. But not before the landowner yielded.

Today, FORAGUA conserves thousands of hectares of watershed, enabling hundreds of thousands of people to drink clean, public water. The path has been neither quick nor pretty, marked by bee stings, cow manure and recalcitrant landowners. Unflinching persistence and smart management have characterized Arturo’s and Francisco’s work in safeguarding water supplies. Their example is ripe for local adaptation – wade into your watershed and start organizing!