COMMONS MAGAZINE

Happiness itself is a commons to which everyone should have equal access.

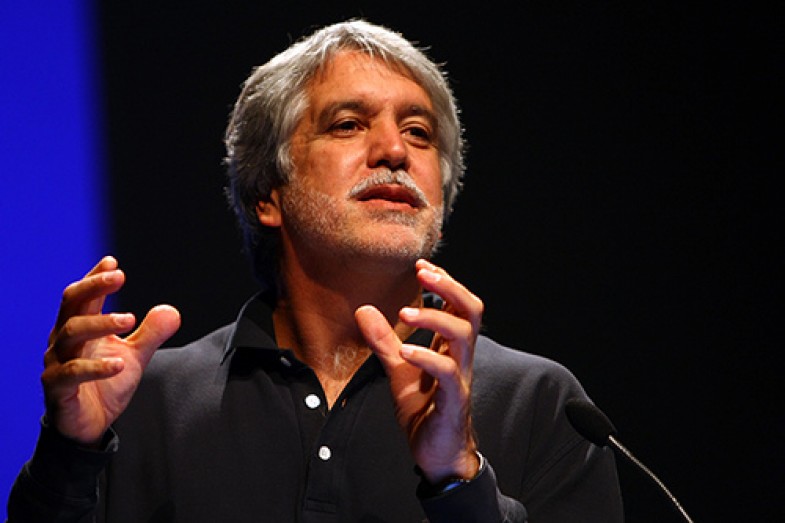

That’s the view of Enrique Peñalosa, who is not, as you might expect, a starry-eyed idealist or philosopher given to abstract theorizing. He’s actually—get ready for this!—a politician, who served as mayor of Bogotá, Colombia, for three years, and now travels the world spreading a message about how to improve life for all citizens in modern cities.

Peñalosa’s ideas stand as beacon of hope for cities of the developing world, which even with their poverty and problems will absorb much of the world’s population growth over the next half-century. Based on his experiences in Bogotá, Peñalosa believes it’s a mistake to give up on these cities as good places to live, no matter how out-of-control conditions appear.

“If we in the Third World measure our success or failure as a society in terms of income, we would have to classify ourselves as losers until the end of time,” declares Peñalosa. “So with our limited resources, we have to invent other ways to measure success. This might mean that all kids have access to sports facilities, libraries, parks, schools, nurseries.”

Peñalosa uses phrases like “quality of life” or “social justice” rather than “commons-based society” to describe his agenda of offering poor people first-rate government services and pleasant public places, yet it is hard to think of anyone who has done more to reinvigorate the idea of the commons in his community.

In three years (1998-2001) as mayor of Colombia’s capital city of 7 million, Peñalosa’s Administration accomplished the following:

• Created the Trans-Milenio, a bus rapid transit system (BRT), which now carries a half-million passengers daily on special bus lanes that offer most of the advantages of a subway at a fraction of the cost.

• Built 52 new schools, refurbished 150 others, added 14,000 computers to the public school system, and increased student enrollment by 34 percent.

• Established or refurbished 1200 parks and playgrounds throughout the city.

• Built three large and 10 neighborhood libraries.

• Built 100 nurseries for children under five.

• Improved life in the slums by bringing public water to 100 percent of Bogotá households.

• Bought undeveloped land on the outskirts of the city to prevent real estate speculation and ensured that it will be developed as affordable housing with electrical, sewage, and telephone service as well as space reserved for parks, schools, and greenways.

• Established 300 kilometers of separated bikeways, the largest network in the developing world.

• Created the world’s longest pedestrian street, 17 kilometers crossing much of the city, as well as a 45- kilometer greenway along a path that had been originally slated for an eight-lane highway.

• Reduced traffic by 40 percent with a system where motorists must leave cars at home during rush hour two days a week. He also raised parking fees and local gas taxes, with half of the proceeds going to fund the new bus transit system.

• Inaugurated an annual car-free day, where everyone from CEOs to janitors commuted to work in some way other than a private automobile.

• Planted 100,000 trees.

All together, these accomplishments boosted the common good in a city characterized by vast disparities of wealth. He’s passionate in articulating the vision that a city belongs to all its citizens, which explains his push for better public transportation, public services, parks, schools, libraries, childcare facilities, neighborhood sanitation, and bike trails.

David Burwell—a strategic analyst with Project for Public Spaces who has long experience working on environmental, transportation, and community issues—calls Peñalosa, “One of the great public servants of our time. He views cities as being planned for a purpose—to create human well-being. He’s got a great sense of what a leader should do—to promote human happiness.”

Several subsequent mayors expanded on his reforms, and the city is now held up as an international model for sustainable innovation. Bogota mayor’s are limited to one consecutive three-year term. Peñalosa ran again for mayor earlier this year, losing according to some observers because his opponent also embraced a quality of life agenda, including the promise of a new subway system.

Enrique Peñalosa has become an international star of sorts among green urban designers, so I assumed he was trained as a city planner and inspired by long involvement in the environmental movement. But the truth is that he arrived at these ideas from a completely different direction. “My focus has always been social—how you can help the most people for the greater public good.”

Growing up in the ‘60s, when revolutionary fervor swept South America, Peñalosa became an ardent socialist a young age, advocating of social justice and income redistribution to anyone who would listen. He studied economics and history at Duke University in the U.S., which he attended on a soccer scholarship, and later moved to Paris to earn a doctoral degree in management and public administration. Paris was a marvelous education in the possibilities of urban living, and he returned home with aspirations of bringing European-style city comforts to the working-class of Bogotá. Several years working as a business mangager and moderated his ideological views but not, he hastens to tell me, his quest for social justice.

“We live in the post-communism period, in which many have assumed equality as a social goal is obsolete,” he explains. “Although income equality as a concept does not jibe with market economy, we can seek to achieve quality-of-life equality.”

Quality of life is not just a phrase to Peñalsoa. He is firmly dedicated to giving everyone in a city more opportunity for recreation, education, transportation and the chance to take pleasure in their surroundings. That explains his emphasis on parks, mass transit, bikeways, schools, libraries and other forms of the commons that enhance people’s lives. And that focus on serving the disadvantaged extends even to streets and sidewalks—which he points out is where poor people who do not have backyards, vacation homes and private clubs tend to hang out.

Peñalosa is proud of how his tamed the automobile in Bogota in order to meet the needs of those who do not own cars. Nearly all cities around the globe accommodate motorists at the expense of everyone else, turning the streets—a commons that once was used by everyone, including pedestrians and kids at—into the the exclusive domain of motorists. In the developing world, where only a select number portion of people own motor vehicles, this is particularly unfair and detrimental to a sense of community.

This feat was accomplished with carrots and sticks. As expected, the sticks—driving bans during rush hour and enforcement of long-ignored laws prohibiting motor vehicles on the sidewalks—drew howls of outrage from a small but powerful group of people, who had always treated sidewalks as their own personal parking lot. “I was almost impeached by the car-owning upper classes,” Peñalosa recalls, “ but it was popular with everyone else.”

The carrots however were embraced by almost everyone. The pedestrian streets, greenways and bike trails he created are well used on weekdays by commuters and on evenings and weekends by recreational bikers and walkers out enjoying the Latin custom of a paseo—an evening stroll.

Another hit is the Ciclovía, in which as many as 2 million people (30 percent of the city’s population) take over 120 kilometers of major streets between 7 a.m. and 2 p.m. on Sundays, for bike rides, strolls and public events. This weekly event began in 1976 but was expanded and promoted by Peñalosa. It now has spread to numerous Colombian cities as well as Quito, Ecuador; El Paso, Texas; Las Cruces, New Mexico; and is being explored for Chicago, New York, Portland and Melbourne, Australia.

Peñalosa’s proudest achievement is TransMilenio, the bus rapid transit (BRT) system that enables buses to zoom on special lanes on that make mass transit faster and more convenient than driving. There are now 8 TransMilenio routes criss-crossing Bogotá. The idea was pioneered in Curitiba, Brazil, in the 1970s but Bogotá’s success showed it could work in a larger city.

Oscar Edmundo Diaz, Senior Program Director for the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), who was Penalosa’s chief mayoral aide, proudly notes that even wealthy people who own cars are now enthusiastic users of BRT. “You don’t want to build a transit system just for the poor,” he counsels. “Otherwise it will be stigmatized, and even poor people will look down on it. If everyone uses it, it will help the poor more.”

Wowed by the success of TransMilenio, six other Colombian cities are developing their own systems. Peñalosa and Diaz have been very influential in spreading the idea throughout the world. In 2004, Jakarta, Indonesia, inaugurated TransJakarta, a Bogotá-inspired BRT line and now features six lines and three under construction. Dozens of other cities around the globe have BRT projects under construction or up-and-running, including Hong Kong; Mexico City, Mexico; Johannesburg, South Africa; Taipei, Taiwan; Quito, Ecuador; and Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. The idea is now spreading to cities in developed countries including, Sydney, Ottawa, Pittsburgh, Minneapolis-St. Paul and even the city known for decades as the world centre of automotive glory, Los Angeles.

It’s not that Peñalosa hates cars. It’s that he loves lively places where people of all backgrounds gather to enjoy themselves— the public commons that barely exist in cities where the cars rule the streets. These sorts of places are even more important in poor cities than in wealthy ones, he says, because poor people have nowhere else to go.

“We all need to see other people. We need to see green. Wealthy people can do that at clubs and private facilities. But most people can only do it in public squares, parks, libraries, sidewalks, greenways, public transit,” he declares.

Peñalosa has been taking this message throughout the world in lecture tours sponsored by the World Bank and the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), a New York –based group promoting sustainable transportation in the developing world.

“You cannot overestimate the impact Peñalosa has had, on a personal level, in ten or twelve countries,” notes Walter Hook, director of ITDP. “He takes these ideas, which can be rather dry, and speaks emotionally about the ways they affect people’s lives. He has the ability to change how people think about cities. He’s a revolution that way.”

“Economics, urban planning, ecology are only the means. Happiness is the goal,” Peñalosa says, summing up his work. “We have a word in Spanish, ganas, which means a burning desire. I have ganas about public life.”

“The least a democratic society should do,” he continues, “ is to offer people wonderful public spaces. Public spaces are not a frivolity. They are just as important as hospitals and schools. They create a sense of belonging. This creates a different type of society—a society where people of all income levels meet in public space is a more integrated, socially healthier one.”