Against the background of banners proclaiming “We Built It!,” speaker after speaker at the Republican convention blasted President Obama for substituting government for the agency of the people. Referring to a comment Obama made at a rally in Virginia about roads and bridges, “You didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen,” Scott Walker, governor of Wisconsin, posed the issue as agency versus dependency.

Voters choice, he said, is between “officials who measure success by how many people are dependent on government” and “leaders who believe success is measured by how many people control their own destiny in the private sector.”

It is worth recalling that Barack Obama struck themes of empowerment in his 2008 “Yes We Can” campaign, bucking modern liberal trends. “I’m not only asking you to believe in my ability to make change,” read the top of the campaign web site. “I’m asking you to believe in yours.”

Obama’s message, resurfacing Lincoln’s view of government as partner and instrument of the people, “of the people, by the people,” as well as “for the people,” can be found here and there in both parties. And it has continued to be championed, in a difficult environment, by the White House Office of Public Engagement, among others in the administration.

But what most struck me about the Republican convention is not agency but its privatization. The work and works of citizenship have largely disappeared.

In contrast, George Bush — hidden away this year — spoke a citizenship language in 2000. “The vision of America’s founders never saw our nation’s greatness in rising wealth or advancing armies,” he declared in his convention speech. He argued that “who we are is more important than what we have,” and posed the question, “what is asked of us?”

Bush envisioned history’s verdict: “A hundred years from now, this must not be remembered as an age rich in possession but poor in ideals.” Bush and his advisers put a call to citizenship at the center of his Inaugural Address. “I ask you to seek a common good beyond your comfort,” the newly elected president proclaimed, “to be citizens, not spectators, to serve your nation, beginning with your neighborhood.”

Bush’s equation of citizenship with service became sentimentalized. After 9/11, his call for “all of us to become a September 11 volunteer,” took backseat to his call for Americans to boost the economy by going shopping. But there are traditions of citizenship — the down-to-earth, everyday public work of building the commonwealth — more about building America than about community service. At the center of these is civic agency.

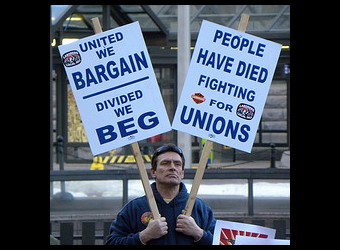

In American history, the vision of a commonwealth built through citizen labors inspired radicals, labor organizers, small farmers and business owners, suffragists and feminists, and those who struggled against racial bigotry and oppression. “The great problem to be solved by the American people is this: whether or not there is strength enough in democracy, virtue enough in our civilization, and power enough in our religion to have mercy and deal justly with four millions of people lately translated from the old oligarchy of slavery to the new commonwealth of freedom,” declared the African American poet Frances Harper in 1875. The argument was that “building America” gave all who co-created the commonwealth a right to equal participation in its public affairs.

Commonwealth has been also a term used regularly by conservative intellectuals, business, civic and political leaders. “The true friend of property, the true conservative, is he who insists that property shall be the servant and not the master of the commonwealth,” declared Theodore Roosevelt in his famous “New Nationalism” speech in 1908.

For such leaders, commonwealth drew on “the commons,” lands, streams, and forests for which whole communities had responsibilities, and in which they had rights of use, and also goods of general benefit built mainly through citizen labors, like schools, libraries, community centers, wells, roads, music festivals and arts fairs. All were forms of commonwealth.

For many immigrants, America represented a chance to recreate a commonwealth privatized by elites in Europe. As the historians Oscar and Mary Handlin observed about the Revolutionary generation of the 1770s, “For the farmers and seamen, for the fishermen, artisans and new merchants, commonwealth repeated the lessons they knew from the organization of churches and towns…the value of common action.” John Adams proposed that every state be called “a commonwealth.” Four (Massachusetts, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky) were so designated.

A similar commonwealth and civic consciousness informed the work of Robert Nisbet, a key figure for modern conservative thinkers. The market alone, he said, celebrates an acquisitive individualism that erodes the authority of the church, the family, and the neighborhood, corrupts civic character, public honor, accountability, and respect for others. Unbridled capitalism, by itself, produces only a “sand heap of disconnected particles of humanity.”

In the Republican convention last week, we have a specter of what that might look like. Citizenship and the commonwealth are disappearing like the cat in Alice in Wonderland.

It is up to all of us to bring them back.

Harry Boyte is Director of the Center for Democracy and Citizenship at Augsburg College and a Senior Fellow at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota.