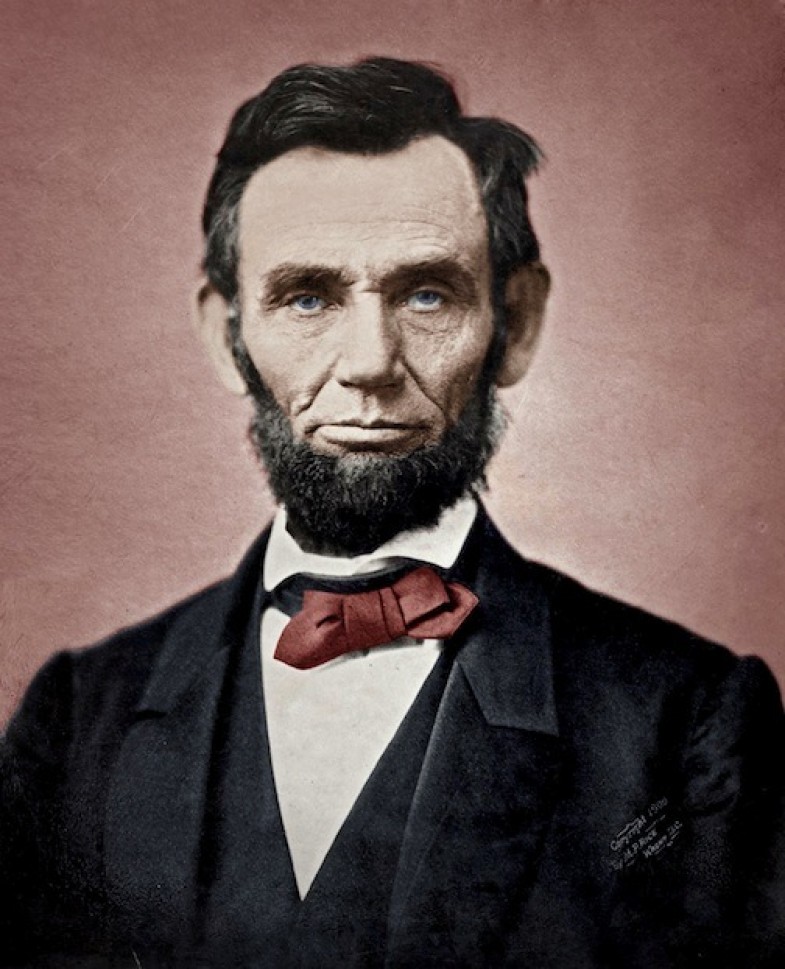

Lincoln is a magnificent movie. But as I left the theatre, to echo Paul Harvey, the late radio commentator, I wanted to know “the rest of the story”.

The movie begins in January 1865, exactly 2 years after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring slaves of the Confederate States “thenceforward and forever free. ”

As Lincoln himself told Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles issuing the Proclamation was a “military necessity. We must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued.” Indeed, Lincoln wanted to issue the Proclamation in July 1862 but Secretary of State William Seward cautioned that the series of military defeats suffered by the Union army that year would lead many to view such a move simply as an act of desperation. The victory at Antietam in September gave Lincoln the opportunity he needed.

The Emancipation Proclamation helped the Union immeasurably. It converted a war to preserve the union into a war of liberation, a change that gained widespread support in key European nations. And by rescinding a 1792 ban on blacks serving in the armed forces, the Proclamation solved the increasingly pressing personnel needs of the Union Army in the face of a declining number of white volunteers. During the war nearly 200,000 blacks, most of them ex-slaves joined the Union Army, giving the North additional manpower needed to win the war. As historian James M. McPherson writes, “The proclamation officially turned the Union army into an army of liberation…And by authorizing the enlistment of freed slaves into the army, the final proclamation went a long step toward creating that army of liberation.”

Abolitionists viewed arming ex-slaves as a major step toward toward giving them equality. Frederick Douglass urged blacks to join the army for this reason. “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”

The movie focuses on one month—January 1865—and the Congressional vote on the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Indeed, it could have been subtitled, “How a bill becomes a law.” The film ends with triumphant celebrations by whites and blacks after the Amendment that ended slavery throughout the nation passed by the razor thin margin of two votes. But for blacks, earning the rights of citizenship was to prove a much more protracted affair.

Gaining the Rights of Citizenship

On April 9, 1865 the South surrendered. On April 15th Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. On April 20, Lincoln’s Vice President, Democrat Andrew Johnson, formerly Governor of Tennessee, formally declared the war over.

The 11 Confederate states would reenter the Union. But left undecided was the legal status of ex-slaves. When slavery was abolished the Constitutional compromise that counted slaves as 3/5 of a person for purposes of Congressional representation no longer applied. After the 1870 Census the South’s representation would be based on a full counting of 4 million ex-slaves. One Illinois Republican expressed a common fear that the “reward of treason will be an increased representation”.

Between 1864 and 1866, ten of the eleven Confederate states inaugurated governments that did not provide suffrage and equal civil rights to freedmen. This was acceptable to Andrew Johnson but not to Republicans like Thaddeus Stevens, masterfully played in the movie by Tommy Lee Jones, who insisted that Reconstruction must “revolutionize Southern institutions, habits, and manners… The foundations of their institutions… must be broken up and relaid, or all our blood and treasure have been spent in vain.”

In March 1865 Congress created the Freedmen’s Bureau to provide food, clothing and fuel to ex-slaves and advice on negotiating labor contracts between freedmen and their former masters. The Bureau, not the local courts, handled the legal affairs of freedmen. It could lease confiscated land for a period of three years and sell portions of up to 40 acres per buyer.

When Johnson assumed the Presidency he ordered any confiscated or abandoned lands administered by the Freedman’s Bureau returned to pardoned owners rather than redistributed to freedmen.

The Bureau was to expire one year after the termination of the War. In January 1866, Congress renewed the Act. Johnson vetoed the bill. An attempt to override the veto failed, marking the beginning of a struggle between Congress and the President over which branch of government had the ultimate authority to oversee Reconstruction—a struggle that ultimately led to the impeachment of Andrew Johnson by the House in 1868. He avoided removal from office by only one vote in the Senate.

In 1865 the Senate and House denied the seating of any Senator or Representative from the Confederate States until Congress decided when Reconstruction was finished.

In March 1866 Congress enacted the first Civil Rights bill, intended to give ex-slaves full legal equality. It stated, “All persons born in the United States … are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States; and such citizens of every race and color, without regard to any previous condition of slavery … shall have the same right in every State … to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, and penalties and to none other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom to the Contrary notwithstanding.”

Johnson vetoed the bill. This time Congress overrode his veto. (Congress also passed a more moderate Freedmen’s Bureau Bill and overrode the subsequent Presidential veto of that.)

In response to the Civil Rights Act, every southern legislature passed “black codes,” which limited the rights and civil liberties of freed slaves. Many stripped blacks of their right to vote, serve on juries, testify against whites and own firearms. Some declared that ex-slaves who failed to sign yearly labor contracts could be arrested and hired out to white landowners.

Congress then passed the Fourteenth Amendment, extending citizenship to everyone born in the United States and prohibiting anyone from being deprived of “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” or denied “the equal protection of the laws.” The Amendment also allowed federal courts to enforce these rights. The Southern states, with the exception of Tennessee and several border states, refused to ratify the Amendment.

A sweeping Republican victory in the 1866 Congressional elections gave Republicans a two-thirds majority, ushering in a ten-year period of aggressive efforts to defend the rights of ex-slaves. The 1867 Reconstruction Act required as a condition of readmittance to the Union for Southern states to ratify the 14th Amendment. The Act also placed the former Confederacy under military rule.

The army conducted new elections in which freed slaves could vote. Whites who had held leading positions under the Confederacy were not permitted to run for office. Republicans took control of all Southern state governorships and state legislatures, except Virginia.

The impact on Southern politics and culture was revolutionary. At the beginning of 1867, no African-American in the South held political office. Within three or four years about 15 percent of all elected officials in the South were black. It may be instructive to note that this was still far below blacks’ proportion of the population, which was over 50 percent in Mississippi, Louisiana and South Carolina, and over 40 percent in four other Confederate states.

Biracial governments wrote new state constitutions, established public schools and charitable institutions and raised the extremely low taxes put in place largely because of the influence of plantation owners. Literacy rates rose dramatically.

In early 1870 Congress passed the 15th Amendment, which finally gave blacks, and other minorities, the right to vote.

Losing the Rights of Citizenship

By 1870 the legal structure was in place to provide ex-slaves full citizenship. The next decades put to the test Martin Luther King Jr’s observation about the human condition expressed a century later. “(W)hile it may be true that morality cannot be legislated, behavior can be regulated. It may be true that the law cannot change the heart but it can restrain the heartless. It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me but it can keep him from lynching me…”

The South proved King wrong. A new civil war erupted, this time not between North and South but internal to the South. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), the Red Shirts, the White League, the White Liners, and other paramilitary organizations operated openly and with clear political goals: the overthrow of Republican rule and the suppression of black voting. They became known as the “military arm of the Democratic Party.”

In 1870 a wave of resulting assassinations in the South moved Congress to pass a law criminalizing conspiracies to deny black suffrage and empowering the President to use military troops to suppress organizations that deprived the rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. Some 20,000 U.S. troops were deployed to enforce the law.

Largely as a result of this widespread violence and intimidation. Democrats had regained control of state legislatures in every southern state by 1877. At the federal level the Depression of 1873, the first major economic collapse in U.S. history and the Republicans’ embrace of a fiscal policy that further contracted the economy led to the Democrat’s controlling the House of Representatives in 1876 for the first time since 1856.

The tight 1876 Presidential election was thrown into the House of Representatives where Democrats agreed to support Rutherford Hayes, the Republican candidate, in return for his promise to completely withdraw federal troops from the South.

The federal courts proved unwilling to enforce the Constitution. In 1873 the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment protected U.S. citizens from rights infringements only by the federal government, not states. In 1876, it ruled that only states, not the federal government, could prosecute individuals under the Ku Klux Klan Act. In 1883, it ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment applied only to discrimination from the government, not from individuals.

Having regained political control and no longer challenged by federal troops or federal courts the South began to systematically strip blacks of the vote, beginning with the Georgia poll tax in 1877. Later they began adding residency requirements, and literacy tests. States conveniently exempted any man whose father or grandfather had voted prior to January 1, 1867 from such requirements.

The impact on black suffrage was devastating. In 1896 in Louisiana, for example, where the population was evenly divided between races, 130,334 black voters were on the registration rolls, about the same number as whites. By 1900 the number of black registered voters had been reduced to 5,320 and by 1910 to only 730.

What came to be known as Jim Crow laws formalized the return of blacks to subordinate status, leading historian W.E.B. Du Bois to famously observe, “(T)he slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

This disenfranchisement of blacks attracted the attention of Congress. From 1896-1900, the House of Representatives set aside election results in over 30 cases where it concluded, “black voters had been excluded due to fraud, violence, or intimidation.” But eventually these investigations died out as Democrats, repeatedly re-elected in one-party states, gained seniority in Congress, resulting in the control of important committees in both houses. Their Congressional power allowed them not only to end investigations into voter suppression but also to defeat anti-lynching legislation and other laws introduced to protect the rights of blacks.

Regaining Citizenship

In the 1940s, for the first time, the Supreme Court began enforcing the 14th and 15th amendments. In 1944 it outlawed all-white primaries. In 1946 it ruled that state laws requiring segregation on interstate buses were unconstitutional. In l950 it required Oklahoma to desegregate its schools. And in 1954 it declared all segregated schools inherently unequal.

The South proved intransigent, notwithstanding President Eisenhower sending federal troops into Little Rock to integrate Central High School in 1957, the first time federal troops were deployed in the South since 1877. Civil rights lawyer Michelle Alexander notes that ten years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision not a single black child attended an integrated grade school in South Carolina, Alabama or Mississippi. Five southern legislatures passed 50 new Jim Crow laws. White citizens councils formed in almost every town. The Ku Klux Klan reasserted itself.

But in the 1960s two new factors came into play. One was the advent of television which allowed the whole country to see Southern police using fire hoses and beating peacefully protesting blacks. The other was the rise of a large civil rights movement. “In the absence of a massive, grassroots movement directly challenging the racial caste system, Jim Crow might be alive and well today,” Alexander writes. “Between autumn 1961 and spring 1963 20,000 men, women and children had been arrested [in civil rights protests]. In l963 alone, an additional l5,000 were imprisoned. One thousand desegregation protests occurred across the region in more than 100 cities.”

In 1963 President John Kennedy announced he would introduce a civil rights bill. In January 1964 the Twenty Fourth Amendment banned the use of poll taxes in federal elections. In July 1964 President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, which prohibited segregation in public places and barred unequal application of voter registration requirements.

In 1965 the Voting Rights Act passed. The Act outlawed literacy tests and provided for federal oversight. Section 5 required states and counties, inside and outside the South, with histories of voter discrimination against minorities to obtain approval from the Department of Justice before changing their voting laws.

The percentage of African American adults registered to vote soared. From 1964 to 1969 the rate in Alabama jumped from 19.3 to 61.3 percent, in Mississippi from 6.7 percent to 66.5 percent, in Georgia from 27.4 percent to 60.4 percent.

Nevertheless, 15 years after the passage of the Voting Rights Act only 8 percent of all Southern elected officials were black, about half the proportion that had held office a century earlier.

Mass Incarceration: The New Jim Crow

As barriers to voting and discrimination against social and economic discrimination fell one by one blacks, and increasingly Latinos, found themselves facing still another barrier to full citizenship: mass incarceration. In her book, The New Jim Crow, Alexander makes a persuasive case that the unprecedented growth in our prison population since the 1970s has been motivated by racial animus. John Erlichman, special counsel to Nixon has described Nixon’s 1968 law-and-order Southern strategy as aimed at “the anti-black voter”. Political scientist Vesla Weaver maintains, “Votes cast in opposition to open housing, busing, the Civil Rights Act and other measures time and again showed the same divisions as votes for amendments to crime bills….”

Ronald Reagan kicked off his Presidential campaign at the annual Neshoba county fair near Philadelphia, Mississippi the site of the 1964 murder of three civil rights activists, declaring, “I believe in states’ rights.”

In October l982 Reagan kicked off a new war on drugs. At the time only 2 percent of the American public believed drugs were a major problem. Between 1981 and 1991 the Drug Enforcement Agency budget leaped from $86 million to $1 billion.

Until l988 the maximum prison sentence for possession of any amount of any drug was one year. The 1988 Anti-Drug Abuse Act imposed dramatically longer mandatory sentences. In 1994 Bill Clinton upped the ante, sending a $30 billion crime bill to Congress and embracing a “one strike and you’re out” policy in which authorities could evict any public housing tenant if a family member allows any form of drug related activity to occur in or near public housing. Congress imposed a lifetime ban on eligibility for welfare and food stamps for anyone convicted of a felony drug offense, even simple possession of marijuana. Students could become ineligible for loans if convicted of a drug offense.

From l980 to 2000 the number of people in prisons or jails soared from 300,000 to more than 2 million.

Two thirds of the rise in the federal inmate population and more than half of the rise in state prisoners was for drug offenses. And as of 2005 as much as 80 percent of drug arrests were for possession.

Human Rights Watch reported in 2000 that in seven states African Americans constituted 80-90 percent of all drug offenders sent to prison. In at least l5 states blacks were admitted to prison on drug charges at a rate of 20-57 times greater than white men even though the majority of illegal drug users and dealers are white.

By the end of 2007 more than 7 million American were behind bars, on probation or parole. Less than two decades after war on drugs began 1 in 7 black men nationally have lost the right to vote and as many as one in four in some states. As legal scholar Pamela Karlan has observed, “felony disenfranchisement has decimated the potential black electorate”.

The Supreme Court once again refused to enforce the Constitution by deciding in case after case that clear statistical evidence of racial bias in arrests or jury selection or judicial verdicts was not enough. The complainant had to prove intent.

Following the 2000 election, it was widely reported that had the 600,000 people convicted of felonies who had completed their sentences in Florida been allowed to vote Al Gore would have easily won the state and the presidency.

In 2008 a black man was elected President and re-elected in 2012. In 2012 more than 70 percent of Latinos and over 90 percent of blacks voted for Obama. Outside of the South he won about 45 percent of the white vote. But in the South he received, on average, only about 20 percent and only 10 percent in Mississippi and Alabama.

The Struggle Continues

Indeed, despite Obama’s re-election and Democrats’ gains in other states, the Republican control of the South tightened. For the first time since Reconstruction, Republicans took over the Arkansas legislature, and won the state’s last U.S. House seat held by a Democrat. North Carolina elected a Republican governor and Republicans gained three more Congressional seats. The last Democrat in a statewide office in Alabama was defeated.

In most Southern states, the margins of victory for Mitt Romney were even larger than the lopsided margins for John McCain four years ago. New York Times reporter Campbell Robertson observed, “The racial and partisan divide is nearly absolute in the Deep South, with a Democratic Party that is almost entirely black and a Republican Party that is almost entirely white.”

Within two weeks of the election the Daily Caller reported, “Petitions (for secession) from Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Caroline, Tennessee and Texas residents have accrued at least 25,000 signatures, the number the Obama administration says it will reward with a staff review of online proposals.” Texas Representative Ron Paul, Former Republican president candidate, lauded the petitions, declaring, “secession is a deeply American principle.”

Meanwhile the Supreme Court has retreated from its aggressive defense of voting rights. In 1966 the Warren Court struck down a $1.50 tax imposed on each voter (equivalent to about $10.50 today). Legislators in southern states defended the tax as a way to prevent “repeaters and floaters” from committing voter fraud. The Court ruled that voting is a fundamental Constitutional right and thus the burden was on the state to prove that a discriminatory law was necessary. It argued that a “payment of a fee as a measure of a voter’s qualifications” violates the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment by unfairly burdening low income, mostly black voters.

In 2007, in a case involving an extremely restrictive voter photo ID law in Indiana, the Roberts Court turned the Warren Court’s 1966 decision on its head by deciding that the burden of proof now rests on those discriminated against to disprove “every conceivable basis which might support” the discrimination. Indiana offered no evidence to support the need for a photo ID. Indeed, it was unable to identify a single instance of in-person voter impersonation fraud in all of its history. The Court acknowledged that as many as 40,000 voters could be at risk because they would have to bear the cost of traveling to distant locations and paying up to $12 for a birth certificate or upwards of $100 for a passport to obtain such an ID, a far greater financial penalty than that imposed by the southern poll tax.

The Roberts Court decision unleashed a wave of voter restriction laws. Thirty states now have voter ID laws, many of them requiring a government-issued ID.

President Obama did win re-election, but the context of that victory is instructive. Elizabeth Drew writes in the New York Review of Books, “On election day, a nationwide coalition of lawyers manned five thousand call centers around the country. Its phone line 1-866-OUR-VOTE…was flooded with almost 100,000 calls from distressed voters saying that they had been told at the polling places that they weren’t eligible to vote, even though they had registered.” Some waited in line for 6 hours or more to exercise their right to vote.

In December 2011 the Department of Justice invoked the Voting Rights Act to block South Carolina’s voter ID law. In August 2012 a three judge panel unanimously held that Florida could not slash its early voting period, citing the Voting Rights Act. After the election this year, the former chairman of the Florida Republican Party, in an interview with the Palm Beach Post noted that he went to several meetings in which Republican officials discussed the damage that early voting, which brought an unprecedented number of blacks to the polls in 2008, had done to the party.

In August another three-judge panel unanimously ruled that Texas’ new state legislative and congressional districts diluted minority voting strength, citing the Voting Rights Act.

Three days after the 2012 election the Roberts Court announced it will hear Shelby County, Alabama’s challenge to the Voting Rights Act. Most observers predict it will overturn the requirement that states gain Department of Justice (DOJ) approval for voting changes.

By all means go see the moive Lincoln. You can even go out cheering the January 1865 victory. But realize that the movie’s triumphal ending did not mark the end of the struggle to gain full citizenship for blacks and other minorities, but only the beginning. Today minorities no longer confront poll taxes and the Ku Klux Klan but newly imposed voting restrictions and racially biased drug laws and a Supreme Court that is indifferent or outright hostile to the rights of minorities. Gridlocked Washington will not come to the rescue. But much of the problem lies at the state level. We need a new massive grassroots struggle such as that which arose in the 1950s and the 1960s, this one to overturn draconian and racially biased drug laws and to eliminate the new wave of law that hamper voter participation. The struggle continues.