In one of his communiqués from the Lancandon jungle of Chiapas Subcomandante Marcos, the spokesman of the Zapatista indigenous people’s revolt that burst upon the world in 1994, referred, of all things, to the Magna Carta. Why the Magna Carta, an eight-hundred-year-old document from Medieval England?

Marcos went on to describe how the ejido, or traditional commons of Mexico enshrined in the national constitution, is being destroyed. He invoked the Magna Carta not only to assert the protections against state power that we associate with this famous English document, but to emphasize the right of people to claim common resources as well.

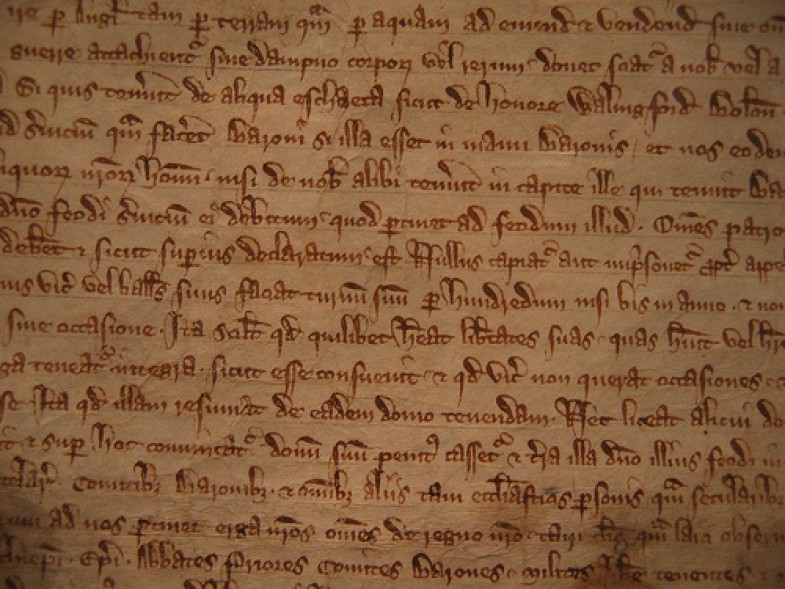

For eight centuries, the Magna Carta has been venerated for its establishment of political and legal rights. The Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution quote its language. Eleanor Roosevelt in her 1948 speech to the UN urging adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, expressed the hope that it would take its place alongside the Magna Carta and the U.S. Bill of Rights. The document has been deemed the foundation of Western democracy and invoked by many, including Winston Churchill, to glorify Anglo-American world dominance and empire building.

There is, I believe, a narrow conservative interpretation of the Magna Carta that stresses “freedom under law,” and a more radical interpretation that establishes the commons and protects the rights of the poor to use it to earn their own livings. belonged to the commoners, and the trees to both. Grazing and hunting, gathering wood for fuel and construction, and picking berries and medicinal plants all sustained country people, especially the poor and widows, who had few other means of support. This is the forest many remember from the Robin Hood legends, based on the Yorkshire fugitive Robert Hod in 1226, who flourished at the moment of the Magna Carta.

The Norman Conquest had disrupted these customs of the forest that had prevailed for centuries. The forest became the sole property of the king, although traditional patterns prevailed in many places. But in July 1203, King John instructed his chief forester, Hugh de Neville, to sell forest privileges “to make our profit by selling woods.” This emboldened his opponents to demand that the forest once again become a commons open to all.

Upon leaving the barons at Runnymede, scarcely had the mud dried on his boots when King John resumed war upon his opponents and began to plot with the pope against them. Innocent III declared the Magna Carta null and void and prohibited the king from observing it. When King John died the next year, the fate of the charter—indeed its whereabouts—was uncertain.

In 1217, the new king, ten-year-old Henry III, was directed by his regents to grant a new charter of liberties, based on the 1215 charter and “also a charter of the forest,” drafted in 1217. But it was only eighty years later when Edward I ordered that the charters become the common law of the land.

What value does the right of access to commons have for people living in modern societies today? Actually the rights laid out in this seminal document of Western law have their equivalents in modern social programs. Piscary, herbage, and pannage, the rights of commoners to fish and graze livestock on the lord’s land, can be compared to food stamps and social security or welfare in the United States. Estover, firebotes, and turbary—the rights to harvest wood and peat from the commons forest—correspond to housing aid and energy assistance.

One aim in bringing this forgotten history of the Magna Carta back to the surface is to put the commons back into view as a fundamental right enshrined in one of the earliest documents of constitutional democracy. Another aim is to rouse today’s commoners to think about protecting the commons through constitutional measures, as is already the case in Mexico, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Bolivia. The Magna Carta is a radical document at the root of our constitutional systems, yet at the root of the Magna Carta is the commons.

Adapted from the book The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All © 2008 by Peter Linebaugh, published the University of California Press. It appears in the OTC book All That We Share: A Field Guide to the Commons .