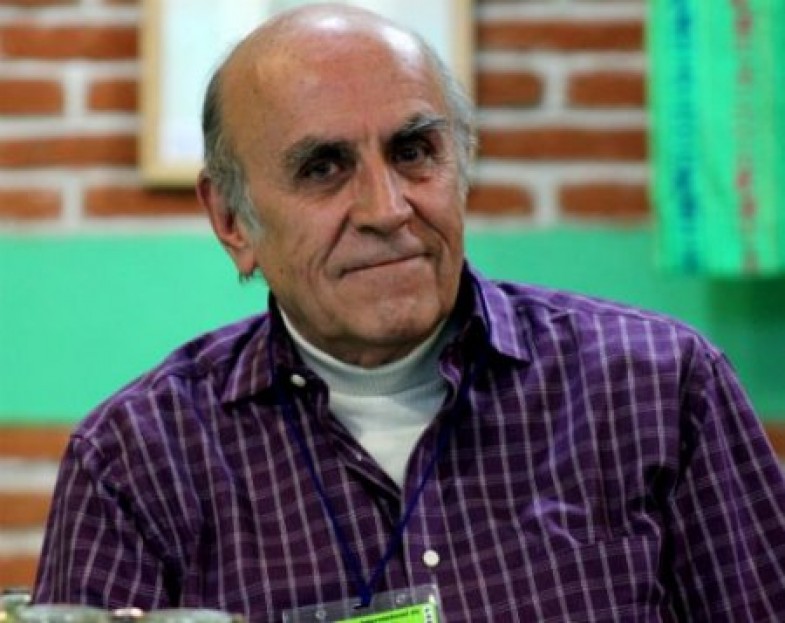

I recently went to Dublin to facilitate a "Thinkery" about the Commons. The event was organized with my Irish co-conspirators, Orla O’Donovan and Mary McDermott, to coincide with the launch of a special issue of the Community Development Journal devoted to the commons. The participants were engaged and the discussions lively. The person who provoked the deepest thinking and most profound reflection was our special guest and chief animatuer, Gustavo Estava, who contributed the article Commoning in the New Society to the journal.

Perhaps the best way to describe Gustavo is through the stories he told Orla, Mary and I when we took a little day trip to the shrine of St. Kevin ninety minutes outside Dublin. Gustavo was born to a middle class family in Mexico City in 1937. A bright student and fervent Catholic, Gustavo wanted to become a priest. But first he needed to prove to himself that God really existed. A wise and patient Jesuit agreed to guide him in what would be his first of many searches for the truth. Over the next two years Gustavo consumed every book his mentor gave him and in the process acquired a deep theological schooling. But none of the priest's arguments sufficed. When Gustavo finally announced that he could find no proof that God existed, the Jesuit responded that this was precisely the point.

From Popular Mechanics to the Cuban Revoluiton

Tired of the books, Gustavo gave up his quest for the priesthood and took up another vocation. As a child, he had always been fascinated by Popular Mechanics Magazine. He loved the spirit of do-it-yourself ingenuity and he loved gadgets. Trading theology for commerce, he began a promising career as a product development manager with Proctor and Gamble.

But another version of truth soon came calling. Inspired by the Cuban Revolution and the spirit of rebellion breaking out throughout Latin America, Gustavo became a guerilla in training. It was easy enough to learn tactics and how to use the weapons, he told us, but the biggest challenge lie elsewhere. A guerilla must accept the moral proposition that it is acceptable to kill other human beings in pursuit of a noble end. Two weeks before the group’s first deployment, one comrade slept with another comrade’s wife. The jealous husband killed the offender and disrupted the already tenuous moral equilibrium of the unit. Gustavo abandoned his career as a revolutionary guerilla.

While continuing his interest in Marxism, Gustavo did something familiar to many former revolutionaries. He decided to change the system from within. In the 1970’s he became one of Mexico’s most influential development officials. He organized dozens of innovative projects and became a government minister. Then in a fateful encounter that would yet again change his life’s trajectory, he met and became a disciple of the maverick social critic, radical philosopher and Catholic priest Ivan Illich, who lived in Mexico for many years.. A close friendship and collaboration followed. (Here is Gustavo's account of working with Illich and engaging with his ideas.)

Illich’s ideas would inform Gustavo’s emergence as the leading proponent of post-development theory and his strong alliance with the Zapatista movement in the 1990’s and the rise of an autonomous indigenous movement in Oaxaca a decade later. (Here Gustavo writes about the Zapatistas and explores post-development in action in Mexico City's experimental Tepito neighborhood.)

A Challenge to Everyone's Assumptions

The experience of travelling with Gustavo over 2 ½ days, was like being in a continuous seminar. We talked over breakfast lunch and dinner, in the car and at the pub. We talked about human rights (which he insists is the enemy of indigenous peoples), the state (an abstraction that is in inevitable decline), capitalism (already dead), democracy (which gives citizens the right to “ask” but props up current systems of control), the individual (which does not actually exist) public infrastructure (dependent on a declining state and must be replaced by more convivial systems), and flush toilets (creates dependence on the state and must be replaced).

Gustavo presented all of these positions in a gentle and learned way. He likes to provoke but is careful to point out his own humanity and imperfections along the way. He draws from multiple traditions—arguing for example that the seeds of modern individualism go back to 11th century theological arguments in the Catholic Church. (And here I always blamed it on Martin Luther!) His critique of centralized technology draws on Ivan Illich, economist E. F. Schumacher (author of Small is Beautiful), The Whole Earth Catalog, and yes, Popular Mechanics. His views on capitalism are deeply informed by Marx as is his critique of all existing revolutions made in the name of Marx.

All of these discussions were “heady.” Mary, Orla and I (as well as the participants in the larger group sessionsof our Thinkery) were happy to ask a question and sit back for a long and fascinating answer. But it wasn’t mostly the “head” that Gustavo appealed to—but to the part of us that is, or aspires to be social. I came away challenged to think anew about my own social and political choices.

Friendship, Hope & Surprise

According to Gustavo, there are three criteria for the good society: friendship, hope and surprise. Their simplicity grounds the abstract into something that can be lived, however imperfectly. At an Irish pub the night before our Thinkery began, Gustavo commented on how quiet the Irish pub is compared to an American bar. The Irish, he claimed, are interested in real conversation which requires listening. Americans like to assert themselves—loudly. When I suggested his observation could well be an overgeneralization, he just smiled. Wisdom does not require empirical proof. It is the provocation that matters.