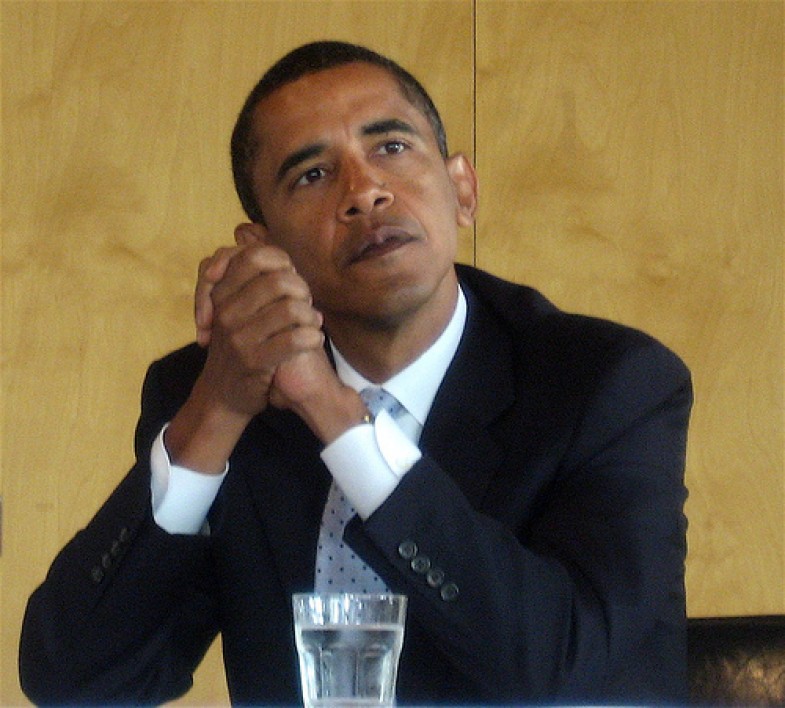

In his acceptance speech on September 6, Barack Obama raised a theme that may have surprised some and pleased others: “We also believe in something called citizenship, a word at the very heart of our founding,” he declared.

His supporters tend to see the president’s citizenship too narrowly, as a riff on progressive politics. In fact, it points beyond partisan wars to the idea of citizenship as the work of citizens, with appeal across the spectrum.

Many who applaud Obama’s citizenship have been stressing the need for better language to describe government action, invoking the language of mutual obligation frequently used in the New Deal. In this view, Obama’s citizenship stems from the school of thought called “communitarianism.” Communitarians emphasize responsibilities to balance rights. They add community service to government action in order to teach mutual obligation.

Communitarians usefully remind us that “we are bound together in a single garment of destiny,” in Martin Luther King’s evocative phrase. But their language sounds too preachy. And their definitions place civic acts as either off-hours voluntarism or the province of public service workers.

But Obama’s citizenship has always had another side: gritty, practical work joining self-interest with public impact. Work holds potential to spread citizenship into many activities and many jobs.

Today “work” has become the rallying cry of conservatives. New York Times analysis of words spoken at the Republican convention found that work outstripped every other word except “Romney.”

Conservatives charge that liberals believe in a nation of “takers,” not “makers,” in the phrase of Arthur Books, president of the American Enterprise Institute.

In The Battle, Brooks argues that the latter group, “the makers,” includes a majority dedicated to values of free enterprise, hard work, and “earned success.” The former, “the takers,” is an intellectual elite comprising 30 percent of the nation and those who follow them. This group is rooted in higher education, communications, entertainment and politics. They seek an expanding government modeled on European-style social democracy.

This analysis was summed up in the phrase “we built it!” throughout the Republican Convention, implying far more than the Obama speech that the Republicans mis-characterized. But citizenship was a rare note at the RNC.

In fact, the idea of “work,” with civic impact as well as individual success, has a rich history in America that needs recalling. Civic work was at the heart of democratizing change and the idea of commonwealth.

For instance, it infused New Deal reform. Cultural figures like Will Rogers and Martha Graham championed a patriotic, work-centered struggle for economic and racial justice, a nation of “liberty and justice for all.” Black poet Langston Hughes’ “Freedom’s Plow” brilliantly conveyed such populist politics:

“Out of labor-white hands and black hands/Came the dream, the strength, the will/And the way to build America./America!/Land created in common,/Dream nourished in common,/ Keep your hand on the plow! Hold on!”

Further, across the partisan divide, many jobs had civic aspects. These were partly developed through courses like Stanford’s “Problems of Citizenship” curriculum in the 1920s and 1930s, which described citizenship as “the second calling” of everyone.

The nation was filled with citizen teachers, citizen business owners, citizen clergy, citizen nurses and doctors, even citizen politicians. These saw their work as woven into the life of communities, and helped to create myriad centers of independent power. A sense of democracy as the public work of everyone, in many settings, was widespread.

Work-centered citizenship ran through Franklin Roosevelt’s speeches. “I propose to create a Civilian Conservation Corps to be used in simple work,” Roosevelt declared to the 73rd Congress. “More important than the material gains will be the moral and spiritual value of such work.”

A focus on work puts citizens, not markets or governments, at the center of the action, and people saw the New Deal as co-created by citizens and government. As Roosevelt said in Cleveland, November 2, 1940, “Always the heart and soul of our country will be the heart and soul of the common man.” It is worth recalling that Ronald Reagan always bragged about his time in the Works Progress Administration.

What happened?

As Duke political scientist Thomas Spragens describes in Getting the Left Right, after World War II liberals replaced respect for work and working people with pity for the poor and oppressed. Distributive justice delivered through government displaced popular agency. These are the markers of a centralizing, technocratic society in which professionals detach from the life of communities.

Such a society turns citizens into consumers.

Obama has pushed back against this consumer view of the citizen. Reflecting on his organizing experiences, Obama wrote in 1990:

“Most [community organizers] practice… a ‘consumer advocacy’ approach, with a focus on wrestling services and resources from the outside powers that be. Few are thinking of harnessing the internal productive capacities… that exist in communities.”

In his victory speech, November 4, 2008, Obama repeated an emphasis on work. “I will ask you to join in the work of remaking this nation… block by block, brick by brick, callused hand by callused hand.” When Time magazine’s Michael Scherer asked what became of such civic partnership, Obama pointed to the calamity facing the nation when he took office: “We had to move very quickly.”

A second term will be different if Obama builds on the call for civic labors in his recent acceptance speech. “As citizens, we understand that America is not about what can be done for us,” he declared. “It’s about what can be done by us together, through the hard and frustrating but necessary work of self-government.”

To deepen work-centered citizenship in serious ways will also require many other actors beyond government. Higher education and others need to generate new centers of democratic power.

We need politics of constructive action across partisan divisions. We need a new generation of citizen professionals who help to create empowering coalitions.

But the call for “the work we do together” is powerful. It points beyond the current paralysis, and intimates hope for civic life, after the election

Harry Boyte is National Coordinator for the American Commonwealth Partnership, Director of the Center for Democracy and Citizenship at Augsburg College and a Senior Fellow at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs.