The historic land-grant tradition of higher education in the United States shares notable similarities to the emerging interest in the “commons”. Having researched scholarship regarding land-grant institutions and recently becoming aware of strategies for a commons-based society, I am struck by their common mission, and commitment to the public interest. This article is intended to introduce land-grant institutions, which celebrate their 150th anniversary this year to the “commoners” in hopes of bringing together advocates for the advancement of our communities and society.

From the perspective of both commons advocates and land-grant institutions, higher education should be a public good-for-all. Many have argued that the rising costs of tuition, student loans, and enrollment practices have privatized higher education. So the original establishment of land-grant institutions returns us to an earlier idea of offering teaching, research, and service for the masses The commons movement calls attention to shared and public goods that “belong to all of us”—of which higher, adult, and continuing education could be included.

Land-grant institutions, since their inception with the First Morrill Act of 1862, have been in a continual process of renewing and transforming their traditional mission. This transformation requires mutual, reciprocal, and shared relationships between institutions and communities. However, many land-grant institutions today express difficulties in quantifying community voices to benchmark, assess, and evaluate significant outcomes and systematic change. Advocates and proponents of the commons-based strategy may regard land-grant institutions as an appropriate venue to do the following:

1) Introduce a commons-based strategy to all land-grant institutions;

2) Serve as the collective community voice that land-grant institutions can assess their service and engagement outcomes; and

3) Make new and lasting partnerships that fulfill the common good of the public, especially higher, adult, and continuing education.

Some specific commons-based actions might include revisiting service-learning programs, community-based research, engaged scholarship, and starting a 21st century “commons-colleges” movement.

Mutual Movement

In the context of American higher education, land-grant institutions has represent a unique set of colleges and universities initially charged to offer a new form of education and learning. Since their beginnings as agricultural and mechanical (A & M) schools, land grant colleges have expanded beyond farming in their mission to serve both rural and urban communities. With federal legislation in 1862, 1890, and 1994, there are approximately 110 U.S. Land-Grant Institutions, at least one in every State and major territory (see sidebar). These institutions range from research universities to Native American tribal colleges, most public and some private, all of them serving multiple and diverse communities.

Before land-grant institutions, education and learning had been reserved for the privileged few, but the hope and promise of these colleges was to open doors for the common people. Over time, the common people would come to include African-Americans (many historically black colleges were added to system in 1890), Hispanic Americans, and Native Americans (many tribal colleges were added in 1994) resulting in land-grant institutions being called the “public’s universities.”

Relating to communities, many land-grant institutions are recognized for their cooperative extension programs, outreach departments, and engagement offices that provide knowledge and expertise for common issues and concerns. The land-grant idea, which has not been fully actualized, does signify a movement toward a mutual “two-way” relationship between institutions and communities, campuses and neighborhoods, educators and learners.

As land-grant institutions now celebrate 150 years of service since Abraham Lincoln signed the First Morrill Act in 1862, there have been concerns about how they remain relevant to the public. Some observers have targeted their historic threefold mission of teaching, research, and service as needing a makeover for the twenty-first century. The upgraded mission would emphasizes learning, discovery, and engagement that underscore the broader agenda of viewing the land-grant mission as more collaborative, reciprocal, and interactive.

Reciprocal Mission

The most discussed issues involving land-grants today relate to service or engagement. In fact, if you were to browse a website of a land-grant institution in any U.S. state you’ll likely find terms including service learning, community service, outreach, or extension. All of these are land-grant lexicon for establishing relationships with the community.

The concern among many supporters of the land-grant mission is that these institutions never go beyond the rhetorical language. In other words, service and engagement may occur, but in words only, and not embedded within the daily practices and procedures of the entire institution. As George McDowell (2001) warned in a book entitled, Land-grant Universities and Extension into the 21st century: Renegotiating or Abandoning a Social Contract, land-grant institutions are in “danger” of irrelevancy, if they do not engage with their communities. These kinds of engagement are what Harry Boyte (author of Everyday Politics: Reconnecting Citizens and Public Life) called “public work,” which searches for real-life answers to what Ernest Boyer, in his Scholarship of Engagement, described as the “most pressing” problems in our society.

These efforts envision service and engagement at land-grant institutions intertwined with the practices of teaching and research; discovery and learning; partnership and democracy. In this way, the work targets the daily actions of all stakeholders including college administrators, faculty, and students. Other practices—such as community-based (action-participatory) research, civic engagement, and collaborative inquiry—emphasize reciprocal and respectful shared-interest between land-grant institutions and the commons-based communities.

Shared Public-Interest

The most significant connection between land-grant institutions and commons-based organizations and movements exists in their shared interest for the public community. How their interests have been applied or expressed may differ, yet their common theme could be a catalyst for future partnership and collaboration.

Advocates for community engagement such as Scott Peters in his work entitled, Engaging Campus and Community, has called for a “meshing” of interests where campuses engage through public scholarship, legitimate relationship-building, and renewing a sense of reciprocity, civility, and democracy. Traditionally, land-grant institutions had assumed an expert role of providing information, science, and technology to farmers and others in the community. However, the expert approach often discounted the knowledge and experience of community members. It isolated the mission of service as “doing good volunteer-work,” thus separating from the missions of teaching and research, both of which have been more recognized and supported by many land-grant institutions.

In other words, the traditional view of service and engagement took on a “one-way relationship” that spurred the Kellogg Commission on the Future of State and Land-Grant Universities to advance both an alternative view of a “two-way mutual relationship” between campuses and communities as well as the renewal of teaching, research, and service through promoting learning, discovery, and engagement. These alternative views highlighted the importance of integrating scholarly work with public needs through sharing interests that benefit both constituencies.

Next Steps for Engagement

In my own studies of land-grant institutions, I found there are various aspects of service and engagement emphasized at different campuses. Practices vary according to location, research activity, and areas of funding, which all together offer a very complex picture of the challenges and dynamics involved. In a market era, driven by measurable outcomes, land-grant institutions are challenged to document their service and engagement—that is, capturing the voices and needs of their community as a whole. Given the diversity of land-grant institutions, one measure may not apply to all.

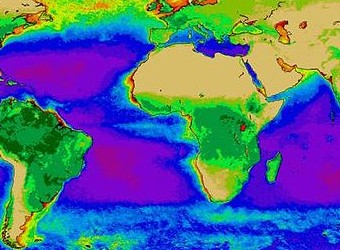

Surprisingly, here is where the commons-based initiative can play a vital and momentous role for land-grant institutions. The commons-based strategy has focused on shared and public goods that “belong to all of us”; some of these areas include not only food systems, water, and environment; but also internet, politics, and the economy. Specific land-grant institutions through cooperative extension programs and their agricultural experiment stations have started this kind of work in local counties and regions. But in collaboration with the projects of commons-based communities, the work could advance beyond a agricultural focus and toward a national and global agenda for the benefit and interests of all.

In short, land-grant institutions are an ideal place to continue the “commons work.” Land-grant institutions were established or supported by federal legislations and funding, which speak to the national policy potential for these institutions. It follows that if any changes could occur, such as introducing service and engagement within a commons-based strategy, the impact of such collaboration could carry across states, territories, even nations.

In addition, these next steps may help many land-grant institutions resolve challenges of benchmarking, assessing, and evaluating service and engagement. Instead of measuring their work project-by-project in the short term, a commons-based strategy could invite documentation of a mutual mission, community-with-community, of those having access to their “common goods,” now and continuing. Land-grant institutions could also provide the common good of higher education-for-all, where every land-grant campus would not only regain their status as the public’s universities, but also become recognized as “commons-colleges.”