Elizabeth Dingmann is the inaugural poetry fellow for Commons Magazine’s new commons-inspired poetry column, UNCOMMON/WORD. She worked with the magazine’s team of poet advisors, guiding the process of selecting poems that will be featured in the column over the next six months.

A graduate student at Hamline University in St Paul, MN, Elizabeth is both a writer and an editor. Her work has appeared in the Saint Paul Almanac, Studio One, Among Women, and DOGEAR, and is forthcoming in rock, paper, scissors. Her poem “Double Bound” was selected for the mnLIT What Light Poetry Project. Elizabeth has served on the editorial boards for rock, paper, scissors and The Water~Stone Review, and we at Commons Magazine have been extraordinarily fortunate to have her experience, insight, and enthusiasm help to guide the launch of UNCOMMON/WORD.

I recently had the opportunity to ask Elizabeth a few questions about her poetry practice and her thoughts on how poetry connects to the commons.

What drew you to a literary life?

I first started playing with words and how they could be shaped on the page as a child. However it was during my undergraduate years that I began to take writing poetry more seriously. I had a wonderful mentor at that time whose name was Sister Eva Hooker. She was fantastic, and even went so far as to set up a special class for three of us who were very committed to our writing. We met at her house every week to read each other’s work and give feedback. We would drink tea with her and discuss poetry. It was a wonderful opportunity.

I then began to think more seriously about poetry—about how to use words and the white space around them to convey different types of written meaning, and how you can do more with poetry than you can with prose. When I realized that there was a program at Hamline University that would allow me to study poetry while continuing my work in publishing and editing, I seized the opportunity.

A colleague once wrote that people can be good at both writing and editing, but they tend to have a brain that focuses best on one of those avenues. I absolutely love both, but my studies have revealed a natural tendency toward editing. Its been wonderful to tie my love of poetry to the editorial experience.

Is the role of editor, the way that you practice it, a solo experience? Or is it a collaborative experience with the poet?

For me it’s a fantastic collaborative experience. Having an editor who is close to the work but who has a different sensibility can be invaluable. A great editor can discover things in the work that the writer didn’t see and in that way help shape things. Sometimes that new piece of insight sends the writer off into a place they might not have gone to on their own.

You sometimes edit books for young readers. What trends do you see with young people and reading? Are video games and social media platforms creating a lack of interest in reading?

I don’t think that young readers are in any way an endangered species!

Young adult literature, especially, is more vibrant than ever. There are some very exciting things going on and great work being published. A growing number of adults are interested in reading stories that were initially written for a younger reader. The work is that compelling.

When I was working at Lerner Publishing Group I was fortunate enough to go with one of our editors to a group called Teens Know Best that’s run at Metro State [University in St. Paul]. It’s one of several programs around that country where teens have the opportunity to read advance-reader copies straight from publishers, which they review. Their reviews are sent back to the publishers. They had so many insightful thoughts about book covers, plots, characters, and other elements of the books, and they weren’t going to pull any punches. They were honest, calling things the way they see them. They’re all very honest readers, and it was always a large crowd. They were really excited to be there. One day the editor I was working with said to me, “Look at that girl, she has The New Yorker in her backpack!” She was probably 17. Experiences like that make me confident that there are plenty of young readers out there.

Let’s talk for a bit about the role of literature in community life, as part of what we share in common. How can we keep books and literature a shared experience within a digital world, where more and more people are reading off an iPhone or Kindle, a personal screen?

That’s a really interesting question in light of new technological developments. I think people who love literature tend to find ways to form community around it, and I’m sure there will be shifts in how people choose to do that as technology evolves. A really great local example is Books & Bars, which is a giant public book club.

Books & Bars was how I made a very large group of new friends when I moved to the Twin Cities. When I was attending it was held once a month at Bryant Lake Bowl. A hundred people would show up and fill the theater. We’d all read the same book. There would be a discussion, moderated by an improv comic who was great at keeping things flowing and re-directing the conversation if things got heated. Books & Bars is a fantastic example of people creating a way to connect over literature. And I believe there are many people who share the compulsion not just to read something, but to read the same thing as others and share that experience.

I see it on a smaller scale, too, with friends recommending books to one another and getting together later to discuss it. People will find ways to have a common experience even if they read the book in a digital format. I think there’s a natural tendency to want to share that experience, that written art form, with other people.

There is also One Minneapolis/One Read. This year it was Gordon Parks’ A Choice of Weapons. Although we didn’t attend one of the public conversations, my husband and I read it, and of course we discussed it. It’s a fantastic book.

That’s one of the great outcomes of having a community reading experience: you wind up reading things that you wouldn’t have if you were just picking and choosing your reading in isolation. It creates opportunities to experience new literature and new writers, and that expands our horizons.

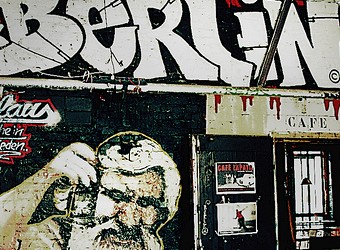

Another example of poetry being a commons experience is the sidewalk poetry in Saint Paul, where the city has invested in making poetry a part of the infrastructure. Now people walking down the sidewalks may encounter verse in a very random and magical way.

Is it stamped in?

Yes, it’s stamped right into the cement creating interactions and small moments that are priceless. Well executed public displays of literature are really valuable to common spaces and public life.

I was in Reykjavik last year where the city has spray-painted poetry on the sidewalk, short poems by Icelandic writers. You’ll come across this little jewel that makes you stop and pause for a moment. It’s really beautiful.

In a society where everyone is always in a hurry, encountering that surprise of a poem on the sidewalk does have an effect on the way a person carries themselves through their day.

The poet Juliet Patterson talked with me about the history of poetry and its origins as a spoken form, a verbal form. There is a rich history of poetry being rooted in song, of words coming out of the body and into space. What’s your take on poetry as a spoken form?

Reflecting on the ancient tradition of the spoken performance of poetry, a form I find really fascinating is the Ghazal, which was an eastern tradition. Rhyme and rhythm were very important, but those poems were meant to be spoken, and they were meant to have audience participation with a rowdy crowd who would be sort of cheering and jeering, depending on how well the poet had executed a particular rhyme or a linguistic turn. That tradition is really visible at spoken word competitions and what you see in rap. There are hundreds of years between the origination of those two forms, yet the way that audiences engage with them is so similar. It’s fascinating.

One of the things that has come up in previous interviews with UNCOMMON/WORDS poet advisors is the role of poetry in keeping language alive. In a time when people’s vocabulary is shrinking, poetry plays a truly crucial role for our culture. Do you agree?

It’s an interesting puzzle that exists in the world of poetry. I think, in general, that poetry feels inaccessible to many people. Some poetry is challenging and difficult to decipher, and some poetry is very plainly-written and beautiful, but the meaning may still be obscure. I don’t think people have many opportunities to explore different types of poetry and find what they like, find their entry point. I’m always interested in the innovative projects and creative ways that writers and publishers make poetry more accessible.

You’ve hit on a crucial point. Poetry often seems like a literary form for the elite or for a certain class of people, not for everyone, and yet we’re living in a very vibrant time. Traditional forms of poetry are keeping language alive through its erudite use, but what about the explosion of spoken word, rap, and more contemporary poetic forms? There appears to be a claiming of language and poetry for modern self-expression.

Absolutely! Literary forms like rap or spoken word poetry are more accessible to people because they’re hearing poetry, rather than seeing a poem written on the page. It’s performed and alive and maintaining a poetic tradition of a certain playfulness with language.

A poet has the freedom to use words in unconventional and surprising ways that don’t happen in prose writing. When I listen to a writer who has found a way to surprise people, who uses words in a different way, or when I hear an especially clever turn of phrase flow into a rhythm or rhyme, it’s exhilarating.