This is the first in a series of essays about art and the commons based on interviews and research in 2007-2008. Watch for more from Rachel Breen in the near future. Editors

How is art a commons? In many conversations with artists and cultural workers from around the country, I had the opportunity to discuss how we might give more shape to the notion that art is a commons. A commons-based society could help increase the ways art provides meaning and value to all of our lives. The current status of the art market – the buying and selling of art at exorbitant prices and an increasingly privatized and exclusive sphere where art is out of reach, literally and figuratively, hurts us all. While most would agree that art is worth so much more than what it can be bought and sold for, (if it can be sold at all) the relentless expansion of the market into the world of art calls us to protect access to making and participating in art. While preventing further encroachment of the market into the commons of art and culture can help insure that people can enjoy and partake of art in the broadest sense, it will also protect artists’ ability to more freely draw from material, ideas and ways of working in order to create anew. This article, the first in a series, seeks to initiate a dialogue about art as a commons and how a common understanding of this notion might help us to sustain and promote creativity and access to the arts.

Chinese Traditional Paper Cut “The King of Hell,” by Ned Young under Creative Commons license, nc, sa, from Flickr

My first encounter with art as a commons took place from 1998 to 2001, when I had the great fortune to live in China and study the traditional folk art of paper cutting. I traveled to many remote villages along the yellow river where people today still live in cave homes. In Yen Chuan, a village four hours by bus from Yan An, the place where Mao mythically holed up with the red army after the long march, we met many aging paper cut artists who make intricate designs with paper, using only a common household scissors and their strong hands. Their mothers had trained these artists, and most stored their collections of paper cuts in between the pages of their children’s old textbooks. Going from home to home, each woman would take out her paper cuts and lay them out so I could look at them. Occasionally the same pattern would appear at a different woman’s house. I asked where the original pattern had come from and there was always confusion with this question. No one seemed to be able to understand the question and no one could even begin to answer. At first I tried different ways of explaining myself– I just wanted to know, which artist had copied the other’s pattern, or who had made the first pattern, seeking to identify the artist responsible for the original or “authentic” design. After repeated attempts to make myself understood it suddenly dawned on me that the process of copying designs from each other was a common, respected and culturally acceptable way of making paper cuts in China – there was no cultural bias about copying and re-making patterns.

Similar to the way quilting and other traditional women’s domestic crafts around the world are taught in a manner that not only encourages but relies on sharing and copying, the tradition of paper cutting represents an art commons. Young girls are taught to make paper cuts by first copying the patterns of others. This can only happen if the patterns are shared. Eventually, as this tradition is passed down through generations, the same patterns make their way into different homes, parts of one pattern are incorporated into new ones and different regions even become known for certain styles and motifs. Some of these beautiful paper cuts are sold in the markets as embroidery patterns to be enlarged upon yet again in another material form and some are used to decorate the homes of the artists. And some just sit in old textbooks in the back of a cabinet, made by artists for the pleasure of engaging in the making process.

Here was the commons, alive and kicking – a stark alternative to the market paradigm. But what meaning might it provide for those of us more fully confronted and surrounded by market-based thinking? For many of us, it is difficult to see around, behind or in spite of. This frontal assault makes it hard for us to imagine how things might be different. Many of us who are thinking about how to amplify the commons both as a paradigm shift and material reality believe that as a starting point we need to see and name the commons as a pre-requisite to claiming it. Language functions to convey meaning. By seeing and naming the commons it can begin to have meaning in our lives.

Meaning is not something that is conjured out of thin air. Artists work within the realm of making meaning visible, audible—communicable. Whether it is through dance, performance, painting, language or music, art provides an experience and through the experience, conveys meaning.

On the Commons explains the commons as “the things that we inherit and create jointly, and that will (hopefully) last for generations to come.” (1) Peter Barnes, a founding member of On the Commons, describes the commons as a river with three tributaries: nature, culture and community.” He explains the main characteristics of the commons as “shared gifts” – things that are received and not earned by the community as a whole, not by individuals. (2)

In its most basic, general way, it is possible to think of creativity as inherent in all humans—something we are born with and share as a birthright, a gift or an inheritance. Kris Maltrud, a dancer in New Mexico describes it this way, “any kind of art—performance, literary, visual—art and its expression is essential and belongs to everyone. I consider creativity a birthright—something that all of us have that we share”. Lewis Hyde, a poet who has extensively explored the idea of the gift economy talks about an artist’s creative energy as the inner life of art—as something generated, in part, by inspiration or intuition, organically bestowed upon humans as a gift, through no effort on our part. (3) Another way of saying this is that artistic expression emerges, in part, from an essential aspect of being human—something we all have “in common”. This is one way we can understand art as a commons.

But an understanding of art as a commons has broader significance when we begin to look at what happens when an artist’s creativity is expressed—when we make or do something with our creative energy. Sal Randolph, a NYC based poet and new media artist describes it this way: “I think of art like any other human cultural activity, making dinner, science, music—all of what we do depends on our cultural context. We wouldn’t know how to make scrambled eggs if a million people hadn’t already done it. The idea of a painting—paint, brushes, stretching a canvas, what you might put on the canvas—these are all things that we do because of our culture. A simple way of looking at it is as social ecology or the way in which we live. We don’t make any thing without being indebted to the commons.” In this way we can understand another layer or level to how art is a commons. The commons is a place where we are linked with all other creative expression: a treasure trove of history and culture that has come before us and which influences how we perceive, envision and comprehend what is possible today.

From The Institute for Infinitely Small Things website.

We might imagine art as a sub-set of the cultural commons—something new that emerges out of various combinations of cultural ingredients—traditions passed down from our families, rituals and ceremonies given to us by our communities and interactions with popular culture that we receive on a daily basis. Joy Garnett, a NYC-based painter reflects a similar perspective with this comment: “Art contains within it a multitude of cultural and historical references, symbolism, meanings, “baggage”, as well as the seeds of that which has yet to come. Art is a bridge between contemporary culture and all that has passed before; it allows for a pooling of information both past, present and future, and hence extends the commons across time. Artists are only partially aware of all the different stuff that actually goes into making their work. This newly created cultural material belongs to everyone. It came out of the commons, once released it returns to it and it will continue to form it. While we each may experience any given artwork differently, art is part of the glue that connects us. Our differing interpretations and experiences of art resonate throughout the commons. The commons is a process, and it is in flux.”

Laylah K. (2003) 26 × 36 inches. Oil on canvas. EXHIBITIONS: TACTICAL ACTION, Gigantic ArtSpace, NYC, Apr-June 2004 by Joy Garnet, image from Flickr cc license, by, nc, sa.

Art can help us see the commons as a resource that we draw from and give back to, consciously and unconsciously. The expression of human creativity that results in an expanding and deepening resource for all to experience, enjoy, learn and benefit from.

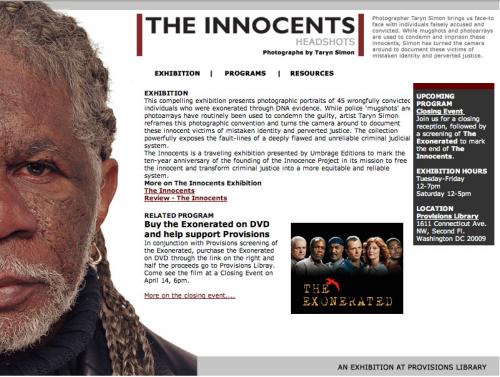

Jane Marsching, a Boston-based new media artist explains it in this way: “At the most fundamental art is about an experience, a communication that people receive, an open gift communication, one that is outside of being constrained by an economic model. That is what makes art a commons as its original impulse.” Art plays a unique role in relation to the commons because it makes visual and communicates about the commons as well as exists as a commons itself. The essential nature of art and culture to human experience and to the very survival of the planet make the commons practical and a necessity for artists and cultural workers along with everyone else. At the same time, increasing privatization and the growing role of the market in influencing art should worry us all, not just artists and cultural workers. Don Russell, the executive director of Provisions Library, an arts and social change resource center, sums it up well: “If you look at human agency, the history of human action you can see that art is one of the first thing we have—the fashioning of things and ideas for social purpose and survival.”

From Provisions Library website.

All art can be considered a part of the commons because creative discoveries inherently benefit humanity in the same way that scientific discoveries do. Art, as cultural, historic and national treasures is something that we all inherit as a people. It exists as a commons. We all own it and have to figure out how to share it. Catherine D’Ignazio, an artist who explores diverse avenues of participation in and distribution of art states, “The question about ownership opens up the notion of a civic sphere where we are participating—creating spaces where people can come together and share experiences and engage in a critical dialogue about the world we live in.” Catherine is also a founding member of The Institute for Infinitely Small Things, a research organization/artists collective in Boston that has a video you can see on their web site titled 57 things you can do for free in Harvard Square. This video shows individuals jumping up and down, playing games and enjoying the park—a humorous artistic work that reminds us that simple non-materialistic ways to enjoy ourselves still exist. Here, the Institute makes the commons visible for us. They help us to see and name the commons and in so doing, help us take a step towards the reclaiming of the commons.

I extend a special invitation to artists and cultural workers to post your thoughts, insights, and your artwork here and to help us see and name the commons. Future articles will explore artwork that makes the commons visible, creates commons experiences, drawsattention to threats or calls for action. Your suggestions, ideas and art are most welcome.

Endnotes

(1) www.onthecommons.org/content.php?id=1467

(2) p. 5 & 117, Barnes, Peter, Capitalism 3.0: A Guide to Reclaiming the Commons, 2006, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco

(3) p. xii, Hyde, Lewis, The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property, 1983, Vintage Books, NY

Kris Maltrud, to be launched later this fall at GiveToArt.org

Lewis Hyde

Sal Randolph

Catherine D’Ignazio

Joy Garnett

Jane Marshing

Don Russell

The Institute for Infinitely Small Things