One of the things that most baffles me about America (and I have lived in the middle of it my whole life) is how the word “independence” is so narrowly defined.

People’s economic well-being can be held hostage by oil companies, pharmaceutical companies, insurance companies, HMOs, and other powerful multinational corporations, yet in political debates independence generally mean just one thing: the absence of government regulation, or any kind of joint citizen effort.

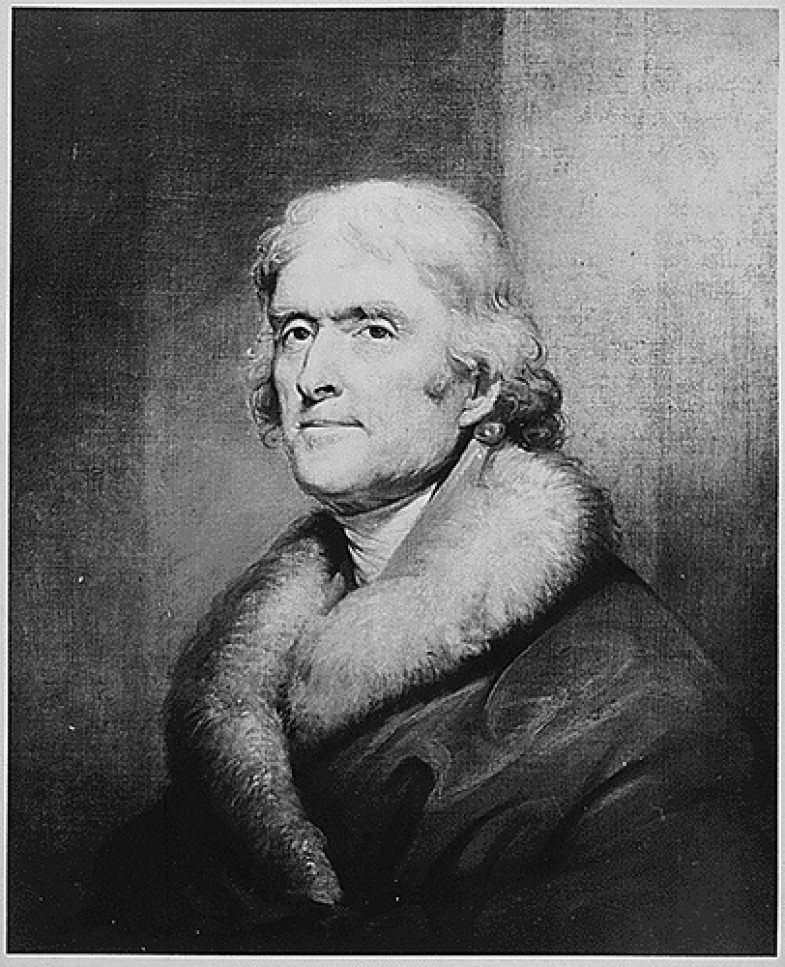

CC license By Marion Doss from Flickr Thomas Jefferson. Copy of painting by Rembrandt Peale, circa 1805. Still Picture Records LICON, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001

I was reminded of this by a headline in the New York Times citing the “independent streak” of Houston residents for the city’s miserably low recycling rate: 2.6 percent, worst in the country, four times less than some others at the bottom of the list like Dallas and Detroit.

“We have an independent streak that rebels against mandates or anything that seems trendy or hyped up,” declared Mayor Bill White, a Democrat who favors expanded recycling in the city. (Actually there’s no law in Houston or anywhere else in the U.S. forcing people to recycle—although San Francisco, ranked at top with 68 percent recycling, is considering one.)

This is surely not what Thomas Jefferson had in mind when he penned the word “independence” in his immortal Declaration. Jefferson embodied a true “independent streak”, working collectively with other American dissidents to “rebel” against the tyranny of the British crown.

Jefferson and his compatriots would be amused (or more likely dismayed) to see that what passes for independence today is a peevish resistance against “trendy and hyped up” chores that might result in a tiny bit more work on trash day. Independence for them did not mean a privatized, selfish focus on individual convenience over the common good.

Although influenced by John Locke and other British philosophers stressing the pursuit of property and the rights of individuals, they still understood the commons as part of the social dynamic that allowed societies to progress.

From communal cattle grazing on the Boston Common (which continued until 1830) to the community cooperation that allowed white settlers to survive on the frontiers of Pennsylvania and Virginia, the commons was central to American life at that time. And for anyone paying attention, the commons-based culture of Eastern Indian tribes, whose Iroquois Confederation influenced the U.S. Constitution, provided another example of the power of the collective cooperation.

No one of that era, including capitalism’s fervent champion Adam Smith, could conceive of a world where the market drove all economic, political and moral decisionmaking. Social bonds created outside the marketplace by people working together to solve common problems is what kept communities together then (and now). To refuse to join a cooperative effort to make the local environment healthier would not be seen as “independent,” but rather as foolish and lazy.

The same is true today.